No FOMO* for Phoma

There are plenty of things about Oregon’s Willamette Valley that are worthy of FOMO, or the *Fear of Missing Out. We have mild winters, fertile soils, & natural beauty abounds. Phoma lingam, however, is not FOMO-worthy. Since 2014, the Willamette Valley has been hit with Phoma lingam, aka Black Leg, a fungal disease that affects all species of Brassica family plants including kale, cabbage, turnips, & many other important food crops, as well as many common weeds such as wild mustard. Black leg causes stunted growth, girdling of the stem, & can lead to great reductions in yield & sometimes plant death. It is estimated that around 10,000 acres of Willamette Valley brassicas were infected in 2014, & similar numbers may have been infected in 2015.

What is being done about it?

The disease is thought to have come in on infected seed, & so in response the Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA) has passed an administrative rule requiring all Brassica seed that will be planted in the Willamette Valley in quantities over 1/2 oz, to have been tested from a qualified, approved laboratory, and to be treated for the disease, even if the test results are negative.

At Adaptive Seeds, seed quality is a priority & we are committed to providing seeds that exceed our customers’ expectations. Even though most of our Brassica varieties are not sold in packages over 1/2 oz, we have decided to test all of our Brassica seed lots, & all of the test results so far have been negative. At this point, we are not treating any of our seed prior to sale.

The ODA’s rule about seed treatment does not specify who must treat the seed (seller or buyer), only that it must be treated. (Also, at this point, the rule is not actively being enforced.) Hot water is the only treatment currently approved for organic systems. Seed must be pre-warmed for 10 minutes at 100˚F, then treated for 15 – 30 minutes (depending on seed type) at 122˚F, then immediately cooled & thoroughly dried (or planted). The margin of error for the temperature of the hot water bath is .1˚F. This, coupled with the time & equipment needs, makes compliance difficult for many growers. Some seeds, such as arugula & cress, cannot be treated with hot water because they release a gelatinous ooze; there is currently no organic option for treating these types of seeds. Nick Andrews of Oregon State University (OSU) Extension has prepared an excellent slide show of the step-by-step process that Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seeds & Tom Stearns of High Mowing Seeds use to treat their seeds.

We do not support the requirement that seeds be treated when a lab test shows that they are not infected. Despite the fact that seed is the primary way the ODA is trying to control the disease, seed is not the source of most infection. Even though there is rampant spread of the Phoma in the valley, researchers are having a hard time finding naturally infected seeds with which to do their research. This is because in order for a seed to become infected, the seed pod must be infected from water-splashed spores. Seed infection is not the result of a systemic infection of the plant, but rather the result of a direct infection on the seed pod. A plant can be infected with Phoma & still not produce infected seed. In a recent presentation, Cindy Ocamb, OSU plant pathologist, reported that in a field with over 70% infection of storage roots in a turnip seed crop, no infected seed was found.

Presented by Cynthia Ocamb, Plant Pathologist, at OSU NWREC Crucifer Meeting, 2014

Cultural Control Methods

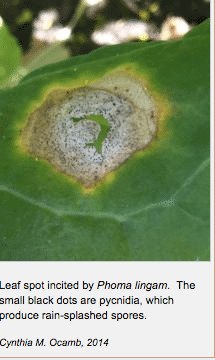

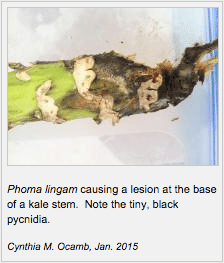

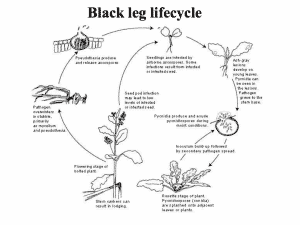

Even with seed testing & treatment protocols in place, Phoma is in the Valley & it will likely continue to spread. Managing diseased plants in the field is the best way to control Phoma. The disease has two reproductive phases. The asexual stage infects leaf tissue & spreads through rain or irrigation events when ascospores are splash-spread up the plant or on to neighboring plants. Leaf infection can reach the plant’s vasculature & become systemic. This stage of the disease can be kept in check by monitoring the field & removing infected leaves.

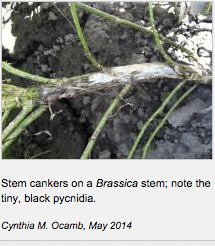

The sexual stage of Phoma is the more difficult to control because infected plant residues can persist in/on the soil for several years, especially in no-till farm systems. In this stage the ascospores are airborne & can travel several miles to infect new fields. The sexual stage requires woody debris to overwinter & reproduce, so this stage of the fungus is primarily found in crop debris from overwintered Brassica crops (which tend to have woodier stems than spring or summer crops). Spores are released when temperatures are between 46˚F & 59˚F. Because the Willamette Valley has vast acreages of Brassica seed production (especially for forage & cover crops) & this is a frequent temperature range for our fall & spring weather, our area has proven to be an easy place for Phoma to get a foothold.

On smaller &/or organic acreages, the sexual stage of Phoma can be controlled by practicing good field sanitation. In smaller plots, this can include removal of all Brassica plant debris from the field. An alternative to removal of plant material, & more appropriate for field scale plantings, is multiple flail mowings followed by shallow incorporation; in biologically active soils the plant debris will break down very quickly & not release spores. Crop rotation, including keeping Brassicas at least 1/4 mile from previously infected fields & not planting Brassicas in the same field more than once in four years, is also effective at limiting the disease. If Phoma becomes a problem in your farm or garden, it is recommended to avoid planting overwintering Brassicas for one year as a way to break the cycle.

Here at Adaptive Seeds, we are practicing all of these cultural control methods, even though Phoma has not yet been confirmed in our fields. It is clear to us that small & organic producers are not responsible for the appearance or spread of the disease. The large conventional fields of canola, forage, & cover crop Brassicas, which are frequently integrated as a rotation in no-till fields, have fostered this epidemic. Still, we all need to do what we can to limit its spread.

The current ODA rule is “final but temporary,” & updates are expected within the next several months. We are involved with a group of stakeholders working to change the hot water treatment requirement. If you are a grower in Oregon that is interested in joining this group, please email us at seed(at)adaptiveseeds.com. We will keep this post updated as the rule changes.

Resources

For more information, please check out the following:

Pacific Northwest Plant Disease Management Handbook: Cabbage and Cauliflower (Brassica sp.) – Black Leg {Phoma Stem Canker} – lots of good photos & basic info on disease identification & management.

OSU Extension Clinic Close-up 1/16: Black Leg, Light Leaf Spot & White Leaf Spot in Western Oregon provides an excellent summary of the situation as well as good photos.

Small-scale Cost-Effective Hot Water Treatment slides by Nick Andrews, OSU Extension, featuring techniques developed by Frank Morton & Tom Stearns, makes on-farm hot water treatment seem not so bad.

Power Point Presentation by OSU Plant Pathologist Cynthia Ocamb – a bit of background on the disease & preliminary findings from 2014.

OSU Extension Clinic Close-up 1/16: Phoma Lingam and Crucifer Seeds

Managing Seed Borne Disease: Brassica Black Leg and Implications for Organic Seed Producers and Industry – webinar from the 2016 Organic Seed Growers Conference, soon to be posted by eXtension.org. Check back soon for this to be linked!

kqa3lo

csk8zg

2broke