By Nick Routledge

” We are all responsible for everyone else, but I am more responsible than all the others.” – Aloysha Karamazov, in The Brothers Karamazov

The defining priority of permaculture is the hitching of our wagons to the evolutionary drift of the landscapes of which we are a part. In other words, we rely more on working with natural processes than in transforming the landscape and our lives through high energy inputs – such as repetitive labor for example.

It’s an approach that puts greater emphasis on ‘perennial’ as distinct from ‘annual’ food crops. Admittedly, this shift in fundamentals is in its cultural infancy, not least because recent historical trends have combined to ensure that the foundations of our diet and the overwhelming majority of research and development associated with it is geared toward high input, conventional, monocrop, annual agriculture. Quite simply, we do not yet possess the range of food crops or experience to supplant this construct.

And yet, behind the scenes, almost completely unnoticed, the visionary food-plant breeders in our midst have been quietly but assiduously devoting their lives to transforming this model. One of the most promising areas of exploration relates to grains – the staple food for the majority of humankind – and the emerging story of the decades-long efforts to perennialize them.

For complicated reasons, the creative tensions which hold all life in balance, appear particularly potentized in efforts to shift grains from annual to a perennial habit. It has not been uncommon to see decades-long breeding programs flounder as the dynamic interplay of genetics runs into a brick wall.

But, as we might hope and expect, the challenge to creatively balance genetics in a way that Nature hasn’t yet managed has attracted the attention of the brightest and the best, and right at the forefront of this global effort is an Oregon native, Tim Peters, most recently out of Myrtle Creek, about two hours south of Eugene. .

Tim has been breeding plants for about 30 years. Passionately devoted to the Great Work, he possesses legendary status among that small tribe who have any idea what he has been up to all this time. Tim has devoted almost two decades work to perennializing grains. In a visit and series of phone conversations over 2004-2005 Tim gave context to my own fledgling efforts to root the perennial grain archetype in my own backyard.

Food Crops with an inherent ability to resist extinction

“Every garden’s like a snowflake, and of course every plant breeder’s approach will differ, too,” observes Tim. And if Thoreau’s dictum “In wildness is the salvation of the world”, holds any weight, then Tim’s life and work has particular relevance for our understanding of ‘what works’. That’s because ever since he began his breeding work as a teenager, Tim has been fascinated by the interplay of food crops with Nature “red in tooth and claw.” Arguably, no plant breeder alive has surfed the interface between domestic & wild cultures as keenly as he.

When I visited him in 2004, checking out his breeding plots included a long drive around the surrounding hills to look in on multi-year breeding experiments in clearcuts and along roadsides, well off the beaten track. It is this decades-long fascination and experience with how food crops interrelate with wild nature that has moved him slowly but inexorably toward his recent successes breeding staple foods with an inherent capacity to resist extinction.

Reconciling paradoxical plant traits

It’s an effort that has been almost 20 years in the making not only because it has taken time for the necessary complements to come together in a genetic interplay with the environment, but also because breeding perennial grains makes for a unique challenge – it involves reconciling some fundamental, but apparently wildly contradictory plant traits. It has been the failure to establish harmony among these ‘breeding paradoxes’ that has put paid to many of the efforts of Tim’s forbears and contemporaries.

For one, the qualities of edibility and survivability are typically at odds with one another – the same qualities that make food palatable to humans, also make them desirable to critters: “Animals are supremely efficient foragers,” says Tim. “They gravitate towards the most edible foods as if by spiritual guidance”. Palatable root crops tend towards quick degeneration and/or extinction in the wild, for example, because desirable roots and the roots’ relative physical proximity to key predators, make them especially vulnerable. Stringy roots with noxious flavor typify plants in the wild, because sweeter genetics get eaten out of existence. Not surprisingly therefore, we see a direct correlation between plant edibility and plant domestication through the centuries. For example, as we bring plants into the protection of our gardens we can actively reduce high tannin levels to increase nutritional benefits, but in the process we remove a trait that makes plants less palatable to critters and prevents them from rotting.

“Now there’s a place for royalty you might say, the delicate things of the plant world,” Tim observes, “but we definitely need crops possessing more of the mountaineering aspect… drought resistance, tolerance to low fertility (which means the ability to proliferate roots in search of nutrients), disease resistance, the ability to continually reproduce in the wild, and suchlike. The more energy a plant has, the more robust it is, the more likely it is to overcome the difficulties in a more natural environment.”

Fundamentals of long-term nutrition

“One does not discover new land without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.” – Andre Gide

A lifetime devoted to breeding a wide variety of food crops in domesticated, fertile gardens and infertile, wild mountain situations has gifted Tim precious comparative insights into the fundamentals of robust, long-lived cultures. “There’s things that time will tell you that nothing else will,” he remarks. For complicated reasons, Tim feel that perennial grains lend themselves to combining many of the essential qualities he has been seeking to usher forth, in a food.

Structurally, for example, they represent a starchy, staple food crop and yet the focus of attention isn’t the plant base – a big plus in circumventing the predatory intent of ground based critters such as gophers. “And although small herbivores like squirrels will topple grains like falling timber, and go stand on the stumps and shuck them with their hands to get at the good stuff, the bigger herbivores, such as deer have to use their mouths. They can’t strip the awns. If they try to eat them they choke to death.” Most perennial grains have awns.

The robustness of grasses, and perennial grasses at that, lends them added ecological horsepower, too. “Grasses pretty much hold their own until trees shade them out in 5-15 years,” Tim avers. “I mean, look out the window. And although there are places where annuals hold their own – deserts for example – in the western states, at least, perennials always have the advantage.” Why? Because unlike annual grains, the perennials photosynthesize more months of the year, and put down a root system that keeps on going deeper, like trees – which gives them the capacity to ‘dig in’, reach sources of nutrients, and create symbiotic relationships over time.

Fast yields and perenniality: the union of opposites

Perennial grains are fast, moving quickly to yield. On fertile soil, sown in fall, they will produce a bountiful crop within a year. On poor soils, within 2-3 years.

The quickness is evident from day one. I have personally witnessed the vitality of perennial grains relative to other plants. They germinate quickly, with great vigor. Almost immediately, the root systems develop an astonishing tenacity. The plants are tough: they survive neglect. This speed to yield on the one hand, and the tendency to perennialize on the other, perhaps marks the highpoint of Tim’s achievement, because it elegantly conjoins what have historically proven to be two highly contradictory evolutionary traits.

Seed making – a trait we wish to encourage in a grain food plant – typically sounds a grain’s last orgasmic hurrah before it dies. A ‘petit mort’ that ain’t so ‘petit’. This fundamental tendency for high yield grains to race to maturity and dry down and hence ‘kill themselves’ naturally sits wholly at odds with a tendency to perennialize.

Tim seems to have found a way through this incompatibility – solving a conundrum that has stymied some of the world’s most tenacious plant breeders for the better part of a century.

Essentially, by stewarding the plant away from ‘focusing on nothing but maturity,’ by encouraging a reversion to a ‘juvenile’ or leafy state a a critical stage of its evolutionary cycle, he as reduced grain’s ‘annualness’.

We can witness this same tendency to revert to a juvenile (vegetative) state in some varieties of brassicas – in the purple and white sprouting broccolis for example – where the inclination of the plant to ‘mature’ early in the year ensures that it does not fall to the hot weather and hormonal and day-length cocktail (of later maturing ecologies) but instead reverts to a leafy state and avoids the run to seed. (These, and other varieties such as ‘Pentland Brig Kale’ harbor genetic promise for those seeking to perennialize brassicas of other forms perhaps.)

Where do the stands stand?

“Is the cycle any easier to accept in the garden than in a human life? In both cases there is a sense not only of obligation, but of devotion” – Stanley Kunitz

To grossly oversimplify his achievement, Tim’s worldwide search for a complementary interplay of genetics gifted him wild perennial grain varieties furnishing the bedrock tendency to perennialize, and highly productive, strongly winter-hardy annual grains. Introducing these patterns to one another in a manner that Nature hadn’t yet orchestrated, Tim has navigated around fatal tillering habits, chromosomal incompatibilities and a slew of other hiccups, to emerge from his lonely decades of devotion with an array of perennial grain material that characteristically sizes up into a winter, thus producing a vigorous seedburst into seedstalks in spring, encouraging reversion to a vegetative state, and the ability to forge on through the years while concomitantly shaking off the challenges of critters, disease, drought, low fertility, and other potentially fatal vectors including that of a larger culture in the grip of a form of mass insanity. Not bad for a self-taught lad.

Tim’s breeding efforts are still a work in progress. He has individual lines and plants exhibiting all the traits he is looking for. What remains, over the short term, is the fine-tuning to develop a stable profile of these complements.

But he has been releasing this material to the public. Perennial grains are almost impossible to come by. Indeed, I believe Tim’s is the only seed catalog in the world making perennial grains readily available for trial – and perhaps the finest examples of the archetype, at that.

Invest now

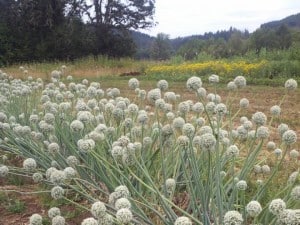

Why consider growing these crops just now? Well, for the sheer beauty of the plants, for one. With stalks tillering to 6 feet in height, they make a striking addition to the character of a garden. And I have noticed the fundamental appeal in my own response, and those of others, to this plant – the puppy dog call. Perhaps this has something to do with the great longevity of the humankind-grain relationship, which touches upon some atavistic nostalgia in the human soul. Sheaves of grain lying around my home always appear to induce an awe of sorts in visitors.

Planting these grains now also represents an opportunity to begin familiarizing yourself with a crop destined to move toward centerstage in our collective endeavors to handhold the emergence of a robust, healthy, regenerative culture. These crops may not be feeding our tribe today. But they will soon. How do we become familiar with the little uniquenesses of growing them? How do we harvest grains and process them as food? How do we do it speedily? These questions can only be answered by doing.

We’re also presented with an opportunity to step into a big story at an absolutely fascinating juncture of its unfolding. In a forthcoming issue of ‘Permaculture News’ I hope to outline some of the simple steps we can take to help play a primary role in selecting and stewarding these plants into more sophisticated/simpler iterations.

And most important of all, perhaps, as we begin embracing an entity that potentizes qualities of vigor, nutrition, hardiness, resistance to extinction and a whole lot more, in a distillation co-designed by Nature at its wildest (and ‘least deceptive’) we are proffered insights into how these archetypal qualities can help inform the Integrity of our own lives. As Jonathan Swift put it: “A man can no more know his own heart than he can know his own face, any other way than by reflection.”

Where to begin?

Tim suggests considering 4 varieties of perennial and annual grains. They are:

* Mountaineer: Perennial Rye

* PSR 3628: Perennial Wheat

* Stephens: Annual Wheat

* White Popping Annual Sorghum

When?

For a bountiful wheat & rye harvest by late July, between October and the end of December is perfect time to plant (seeding between January & April will give you a harvest later in the year, but with much reduced yields). Seeding into flats, 3 seeds per cell, & culling back to 1 allows you to begin selecting for vigor from the get-go. Transplant out between mid-Dec & February onto 6″-12″ squares. The more room the plants have the more they will tiller.

Where?

Plant into as clean a ground as possible. Once the plants are established, it is easier for them to fend for themselves. Balance is necessary, but be aware that much as most current human ailments stem from a culture of excess, so fertility can be an enemy of life to plants. Sorghums excepted, Perennial grains tend to live longer on poorer soils (Mountaineer 2-4 years on rich soil: 7-8 on poorer soils). Planting alongside a gravel driveway makes sense.

For the purposes here, treat sorghum as an annual Spring sown grain. Sow indoors Feb/Mar & transplant April or direct sow post frost. Grind & use like corn-meal or corn flour.